Loy Luo: When Abstraction Complicates Culture

by Jonathan Goodman, February 14, 2024

Loy Luo, now living on the edge of Chinatown in New York City, spent roughly twenty years in Beijing before moving to America. A mid-career artist, Luo has several beautiful bronze statues that she made and stored in China, but the body of work I will be discussing–a group of paintings Luo finished in her studio in Chinatown, a large space in an office building on Mott Street, revives the by-now nearly historical debate of cultural influence from different places and their ability to advance or, sometimes, overwhelm the work of someone making art from far away. It is not an easy discussion, as this kind of exchange, aided by travel and the transportation of objects, has been going on for a long time.

But today, because of the swiftness and ubiquity of the Internet, the notion of influence carries a weight we would not have thought possible before. Eclecticism has become integral to the practice of painting and sculpture today. Luo, who has lived in New York City for four years, is, like all of us, being bombarded by the intellectual traffic of others, whose ideas, feelings, and understanding of form may well be different from our own. It becomes the painter’s job to incorporate these alterations in thought and practice, making them an entirety that reads smoothly but also with weight–as if the discrete articles were inevitably meant to form a whole.

But this thinking also introduces a challenge. Usually, and for a long time (since the romantic period in the West), the fragment has been better received by viewers than the polished whole. Eclecticism, by virtue of its various elements, is oriented toward discrete parts that support the notion of a fragmented object. As we shall see in Luo’s paintings, her art remains an abstract endeavor. Additionally, words will sometimes add intricacies of meaning to the works’ surface. Nature plays a role in Luo’s art as well. Regularly there is the suggestion of flowers. The Chinese language is often used as a support for the painting, which can include poetry or philosophical writings as evidence of the artist’s interests beyond painting. It is also true that the physical shape of the characters alone can play a visual role. And the decorative elements, seemingly floral, have also been studied by Luo. They incorporate elements that resemble conventional nature–blossoms on a branch. Luo does not consciously proclaim the connection, but for a Western writer, the tradition of nature in Chinese painting is so strong as to inevitably lead us to a Chinese view of the painting–this despite the English words that make their way into the composition.

We can ask, how hard is it to remain true to our background when it is thousands of miles away? We need to remember, too, that New York City has been a center for painterly abstraction since a bit before the early 1940s when artists like de Kooning, Pollock, and Gorky led the way in lyric abstraction. In keeping with her stay in New York City, Luo’s work possesses considerable lyricism, often in a nonobjective sense. But Luo’s paintings present an ethereal experience that Western practitioners of art when taken over by Asian influences, produce in their work an expansive egotism that cannot match the understated elegance of the Chinese artist’s hand. One must be wary of over-categorization, especially now; images–and cash–travel the world in moments thanks to the Internet. This inevitably turns the matter of influence into something less than inspiring, as well as influencing too heavily the pricing of the work. Still, visuals making use of the artist’s classical traditions remain resistant to their historical erasure. Art is capable of lasting forever, as we can see from the shards still found in the deserts spots of ancient cultures.

In the long run, it matters little what our affiliations are–culture has become too broad in its contextual alliance to current work, making it very difficult to specify connections. We borrow across time and place so that now it is very hard to distinguish one culture from the other in art. Luo’s white paintings often incorporate the Chinese character as a structural and thematic display–we can see this from the quotations she takes from Buddhist sutras. It is clear from the start that the sutras are in no way an indication of Western culture. But three paintings, each with a beautiful background color, including jade green and rose pink, move away from the written toward a description of the world outside, through color alone. Luo, as happens with all of us today, must manufacture a natural lyricism that stays true to her past. So her style cannot come to her easily. The painters of classical times were nearer to a merger of feeling and idea than we are now when the emotional and intellectual perception of such a lyricism was new and developing into greatness. Luo’s craft is good enough to do so, making it clear that nature is a permanent part of Chinese art in general and her art in particular.

Abstraction, Luo’s forte, is a more intricate problem, given the artist’s extended stay in New York, where the gut feelings of modernist abstract expressionism began. Sadly lyric abstraction has become an American cliche, having taken over what used to be a genuinely innovative style. Luo’s background as a Chinese artist–she has degrees from undergraduate and graduate schools in Beijing–has transformed, even if only slightly, Western abstraction into something that looks to the Chinese character and the Asian understated comprehension of nature. The flowers we find in her art demonstrate her connection to Asia. Doing so provides her with a way out of the dull repetitions of expansive abstraction. The merger of Chinese imagery and language with the inchoate, often unformed shapes of abstraction is hard, but we are working at a time when such connectedness has been presented to the point of becoming repetitive. It is Luo’s job to join one tradition with the other, as hard as that may be.

So Luo’s presentation here, of a group of works at once Chinese and Western, figurative and abstract, amounts to a show in her studio in Chinatown. The ones I will address are two white paintings, both with writing (in one case, the placement of the characters curves like a canopy on the composition's upper right; and on the other, the orientation of regularly placed characters cover the canvas). Then there are three works oriented toward traditional scenic painting, followed by a dark brown, slightly reddish work filled with characters determining the meaning of a Buddhist sutra. Together, the works are more truly indicative of a Chinese sensibility; the paintings with characters coming from sutras prove this, as does Luo’s sensitive handling of the objects and effects of nature. Can a painting true to Chinese culture be made in New York City’s Chinatown?

Half Dimond Sutra, 2023, Mixed Media, 60 x 84 inches

abstract Theater A-8, 2021, Mixed Media, 60 x 84 inches

Heart Sutra-1, 2023, Mixed Media, 60 x 72 inches

Can the culture be carried over, successfully, into a world where the values behind Asian culture are not to be found?

These are difficult questions. Fusion may well be better suited to cooking than to art. Yet fusion has become an acceptable art practice, followed more by Asian artists than Western ones–at least in painting, if not in avant-garde art. Despite the sometimes extravagant beauty deriving from a varied approach, a good deal of work by Luo owes its strength and sensitivity to Chinese painting traditions that are recognizably so. Again, we must recognize Luo’s insistence that she is painting abstraction, and there is a good chance that this may be at least partly true. But for this writer, the deeper truth has to do with the intimations of classical culture and its greatness in figuration–the result of a visionary restraint, based on realism, that took place a long time ago.

Maybe the most important aspect of abstraction, in addition to its contrast with imagery taken from nature, has to do with the ability of nonobjective art to influence style across cultures. This means that fine art is no longer bounded by a particular history, but, instead, adds to the complicated proliferation of styles characterizing contemporary work. Luo, then, is not necessarily in a bind. Her abstraction may be Chinese in feeling, but it also participates in a formality that began in Europe but shifted to New York City, where it has been established since the middle of the last century. Although Luo comes late to this tradition, she has internalized a manner of working that reinvents Western nonobjective art in light of Chinese poise and descriptive truth in painting. This is moving and in Luo’s case has resulted in real esthetic success.

Guilin 2 (2023) is a white painting, decorated by a curtain of characters on the upper right. These characters describe a building process for ships. The center of the painting is cast in a rough white, like the rest of the composition. In the lower left, toward the bottom, a thin stem ends with a rose at the top. Next to it is a squared set of characters that is hard to decipher. The painting is beautiful in design, and, additionally the existence of meaningful, not decorative, characters results in yet another layer of significance–intellectual rather than visual.

Heart Sutra 3 (2023), another painting that is as much an intellectual activity as it is art, looms over us in a tall white rectangle. The surface is rough with bits and pieces of brown and red dotting the work’s landscape, which is itself rough and covered with individual characters that are a bit difficult to make out, given the bumpy exterior. As it turns out, Heart Sutra 3, a Mahayana Buddhist text, emphasizes compassion as a vehicle for inner freedom. Perhaps that freedom is suggested in the textured disconnects in the surface of the painting, whose whiteness can suggest purity and whose characters spell out portions of the text. In one way, it is an impenetrable wall between daily life and enlightenment; in another, it is a facsimile of a window open to perception driven by the emotion of kindness. Luo is regularly ethereal in her outlook.

Half Diamond Sutra (2023), is powerfully colorful with its background of jade green. But the painting is made complicated by inserts–a group of irregularly edged white areas on the far right, and in the middle right, a long, thin stem with a rounded flower-like cup attached. The diamond sutra addresses the spiritual attainment brought about by starvation–not an insight most Westerners would appreciate! But the painting’s indirect, visionary glory may be teaching us that absence, a kind of visual starvation, is the equivalent of the denial of food. Luo’s devotionally driven work, usually rough around the edges, carries with it the capacity for spiritual change, surely a major goal of Buddhist thought.

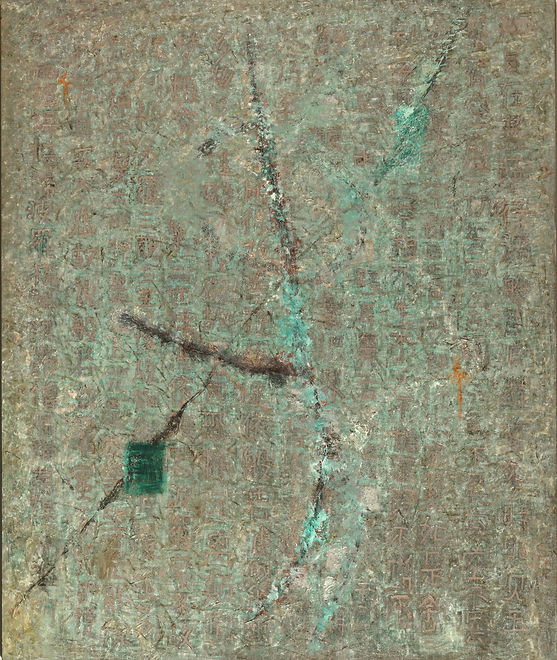

Heart Sutra 2 (2023), a large, grayish painting made in 2023, is composed of individual squares, each holding a character belonging to the religious text. In the middle are two narrow, vertically aligned appendages, with a thicker brown line crossing the sticks horizontally. At the lower end of the left stick is a small green book-like appendage. We may not know what these visual embellishments are, but they decorate and complicate usually simple backgrounds. We know that the Heart Sutra 2 is a piece of writing whose most famous saying is “Form is emptiness, Emptiness is form.” This somewhat opaque aphorism emphasizes the mutability of an emptiness that has been filled, but also the truth of form made into a void. Their mutual exchange becomes the support of the given world. Again, Luo addresses metaphysics carefully, with an eye for the ethereal, the barely known.

Heart Sutra 1 (2023) is a dark brown and gold painting with black stripes dividing the painting space into irregular areas. White characters spell out part of the sutra’s writing; the contrast between the thin white lines of the characters and the muted darker tones painted behind them results in a startlingly vivid work of art. Most Westerners don’t know how to read Chinese; only a few may know a bit about the sutra itself. But the point is that the painting stands on its terms, suggesting an abstract stance to the Western (and, perhaps, also the Asian) viewer. Abstraction is key to Luo’s art, but so are the texts she quotes. The religious nature of the writing Luo uses intensifies the gravitas of her motive, although, to people who cannot read Chinese, the characters remain inherently obscure.

Luo is taken with the Buddhist texts of her culture; they stabilize and substantiate the art–but only if you can read the text. If you cannot, then the characters become visual assertions, to be appreciated for their beauty related to form. The characters might then be considered small paintings, and the word “pictograph” in English describes Chinese writing. Luo comes from a brush culture, and so the facility of her hand was learned at a very young age.

Is it possible to bridge old traditions with new ones? The question must seem a cliche to many. But the abstract elements in the archaic Chinese culture are genuine; they likely lead to a more refined sensibility, perhaps, but the persistence of the past even now remains true. Not all of us looking at contemporary art are looking for archaic impulses, but this has become one way of invigorating art too reliant on recent advances, which can get stuck in the present. Luo’s sensibility, evident in her two-dimensional works and also her innovative three-dimensional ones, looking for a place of restitution–a site in which the old and the new merge. Her attempts, quite successful, address a point of view in which historical time is not as important as the moment we presently carry. Still, Luo possesses a flair– the result of a visionary synthesis of time and place. This is why the art is so good.